The Georgetown Experiment.

The mother of all NLP hype.

Why this series?

It’s interesting to see how the AI field has rapidly evolved. What’s more interesting is to understand its progression. What determines the context window size in a transformer model? Why does training to predict the next token generalize across tasks? Why do we break down words into subwords before training? Why did researchers even care about a computer understanding human language? We can pick a random NLP textbook and get some answers. However, I want to understand and experience the challenges that previous researchers faced, which drove them to introduce specific components, as well as explore the alternative methods they considered. What trade-offs did they make? And how did their solutions evolve into the more sophisticated algorithms we have today? Hence, I’m making this series where I revisit historical NLP algorithms and their implementations. From 1954 to 2024, from rule-based approaches to transformer models.

Motivation?

The first in this series is the Georgetown Experiment, an early attempt to evaluate the feasibility of machine translation. During the Cold War, intercepting and translating communications of the Soviet Union became a pressing issue. The urgent need to translate large volumes of documents quickly highlighted the limitations of human translators, sparking interest in automated solutions.

Warren Weaver, a pioneer in the field, reached out to Professor Norbert Wiener of MIT to discuss the possibility of machine translation. Despite the negative response, Weaver remained undeterred and went on to write The Translation Memorandum, outlining the challenges and potential solutions for machine translation. This memo ignited widespread interest among researchers, culminating in the first-ever machine translation conference at MIT in 1952.

One of the key figures emerging from this conference was Leon Dostert, who became determined to assess the practicality of machine translation through a hands-on experiment—the Georgetown Experiment.

Approach?

Translation is much more than simple word to word mapping. Each language has its own grammar, syntax, and semantics, which shape how ideas are expressed and understood. To bridge these differences, linguists developed intricate sets of rules and structures.

The key innovation of this experiment was in simplifying the machine translation challenge into two fundamental decisions:

- Selection Decision

- Rearrangement Decision

The selection decision addresses the ambiguity that arises when a single word can have multiple meanings depending on context. Take the word “bank,” for instance—it could refer to the side of a river or a financial institution. The task here is to choose the correct interpretation based on the surrounding text, ensuring the translation accurately reflects the intended meaning. Looking at the individual word provides no signal of what the actual meaning could be. However, once the context is taken to account, the meaning becomes immediately apparent.

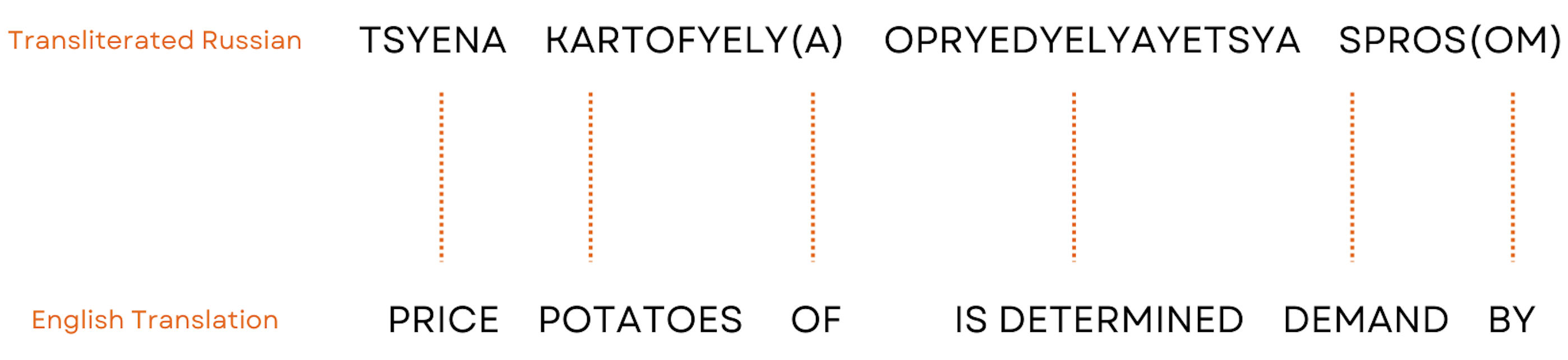

The rearrangement decision tackles the issue of varying grammatical structures across languages. Since languages often follow distinct word orders and sentence structures, simply translating words in their original order would result in confusing or incorrect translations. This step involves reorganizing the translated words to align with the grammatical rules and natural flow of the target language.

These two decisions were encoded by assigning specific codes to each word. Linguists compiled a dictionary containing 250 words (stems and endings), along with their corresponding meanings and codes. These codes served as guides for both word selection and arrangement within the translation process. A set of six rules governed how words were to be reordered in the sentence, as well as which meaning to apply when dealing with words that had multiple interpretations. This system allowed the machine to handle both the semantic choices and the structural adjustments needed for accurate translation.

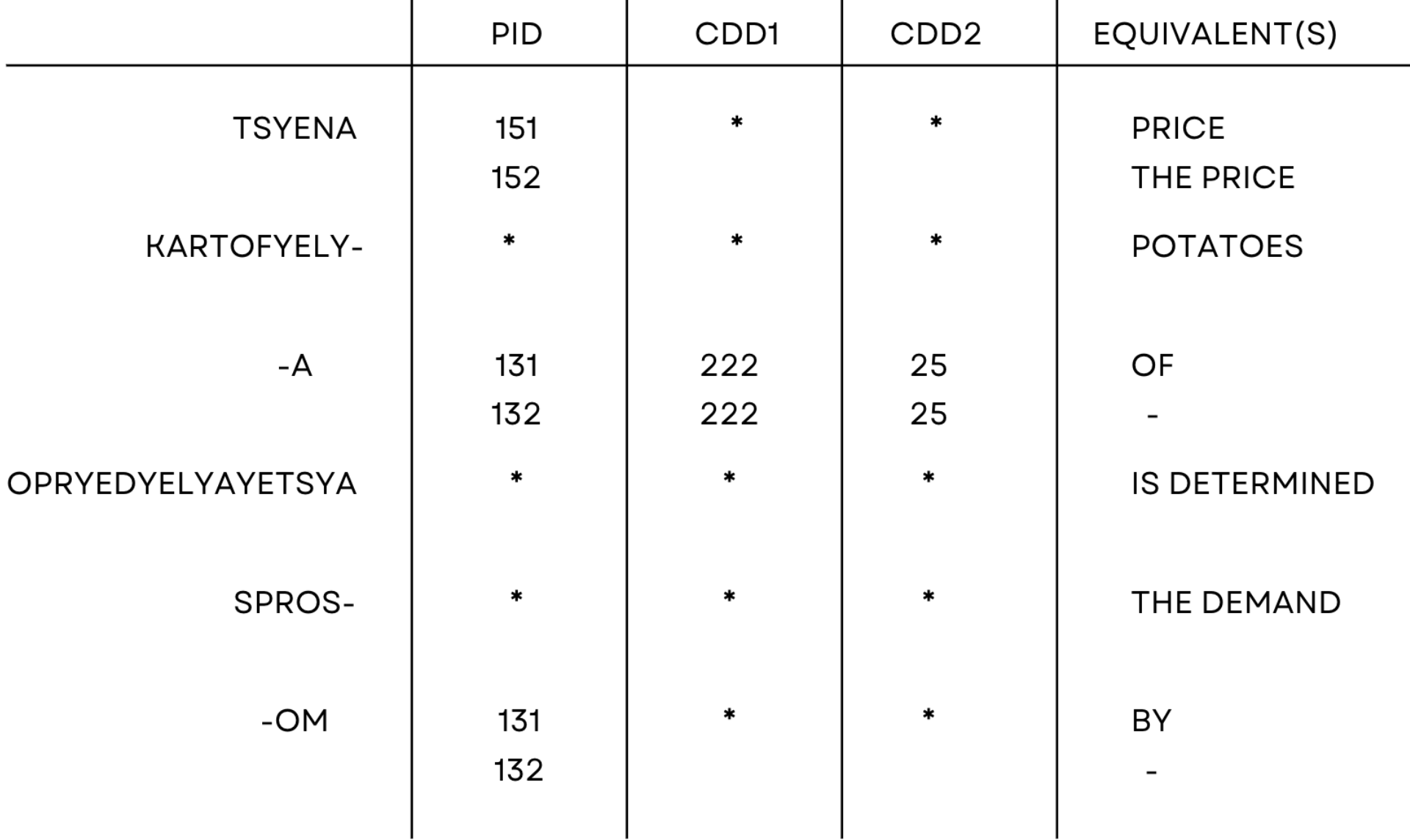

Three codes were associated with each word:

- PID (Program Initiating Diacritic): indicated which of the six rules was to be applied

- CDD1 (Choice Determining Diacritics): indicated what contextual information should be sought to determine selection of target words

- CDD2 (Choice Determining Diacritics): indicated whether words were to be inverted or not in the output

The PID code associated with the word in focus indicates which rule to apply. In the example above, the first word has a PID code of 151, which triggers rule 5. This rule checks whether the CDD2 of the next complete word or partial word (if not found in the next complete word) equals 25. If it does, the second English equivalent is chosen; if not, the first English equivalent is used, without altering the word order in either case. Similarly, the remaining words, whether complete or partial, are translated in the same manner.

Conclusion

This rule-based approach was limited to 60 carefully selected test sentences, chosen by a team of linguists. The dictionary used contained 250 words along with their corresponding English equivalents. While words with multiple meanings were considered, only two meanings per word were included in the dictionary.

Despite these constraints, this approach introduced key concepts that are still foundational today:

- Using surrounding context to determine the meaning of words remains a crucial element of modern NLP systems.

- The concept of breaking words into complete and partial forms is echoed in modern NLP through tokenization, where words are split into multipe subwords.

This experiment sparked widespread interest among researchers and led to the first wave of NLP hype, which lasted about a decade. In 1966, the ALPAC report sharply criticized the lack of significant progress in machine translation research over the previous decade. As a result, the U.S. government drastically reduced funding for the field, contributing to the onset of the first AI winter.

Project code can be found here

References

- W. John Hutchins. 2004. The Georgetown-IBM experiment demonstrated in January 1954. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas: Technical Papers, pages 102–114, Washington, USA. Springer.

- Sheridan, Peter B.. “Research in language translation on the IBM type 701.” (1955).

- Garvin, P.: The Georgetown-IBM experiment of 1954: an evaluation in retrospect. In: Papers in linguistics in honor of Dostert, pp. 46–56. The Hague, Mouton (1967) ;reprinted in his On machine translation. The Hague, Mouton , 51-64 (1972).

- ALPAC: Languages and machines: computers in translation and linguistics. A report by the Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee, Division of Behavioral Sciences, National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences – National Research Council (1966).